Inside Vexcel: Adaptive Motion Compensation – Motion Happens. Blur Doesn’t Have To.

This is the third article in the Inside Vexcel series, diving into why sharp aerial imagery depends on more than hardware.

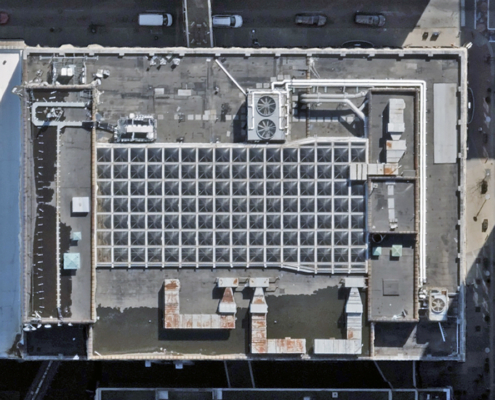

Clear imagery doesn’t happen by accident. In aerial mapping, crisp, high-quality imagery is a result of careful engineering decisions, smart software, and an understanding that an aircraft moves quickly above a still landscape.

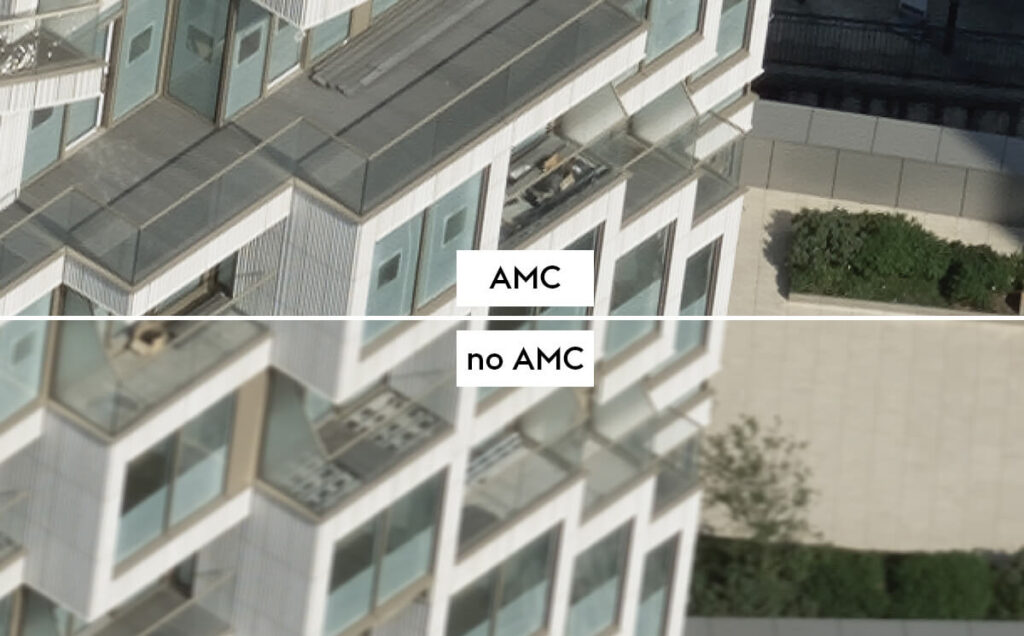

Even with today’s advanced sensors, aircraft movement during exposure can introduce blur that quietly degrades image quality. That blur doesn’t just affect how an image looks. It affects what you can extract from it, how confidently you can measure from it, and how well it supports downstream products like 3D models, orthos, and AI-driven analytics.

Thats why Vexcel Imaging developed Adaptive Motion Compensation (AMC), a software-based technique that restores clarity at the source. Available since 2020 and running across all 4th generation UltraCam systems, AMC is designed to deliver sharp, consistent imagery even when flight dynamics and terrain get complicated.

Where Blur Really Comes From

Motion blur in aerial imagery isn’t a single problem. It’s a combination of effects happening at once, often varying across the same image.

Three main factors create motion blur in imagery:

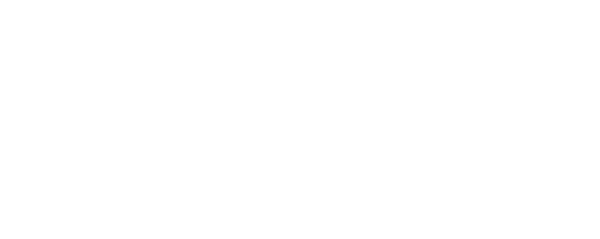

Forward Motion Blur

The aircraft travels during exposure. Over flat terrain and in nadir imagery, this blur is usually uniform across the sensor.

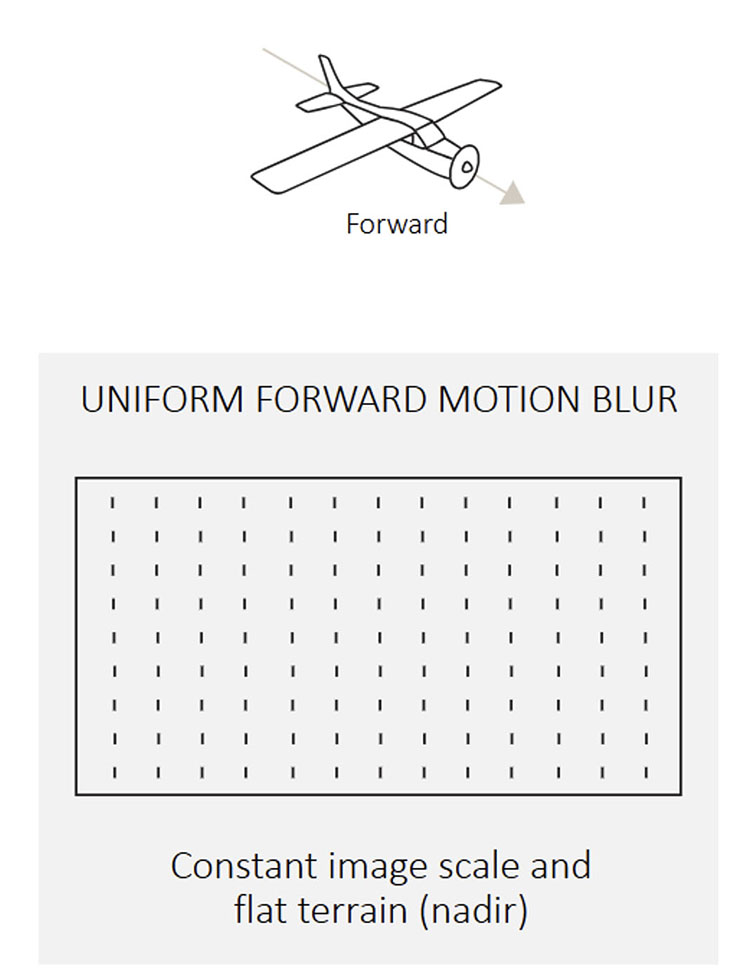

Non-uniform forward motion blur

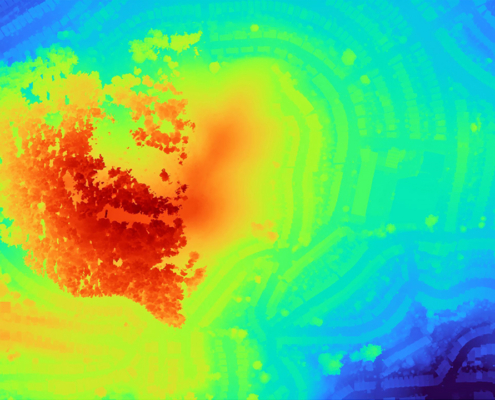

Scale varies across an image, especially in oblique views or in areas with large terrain differences. Closer objects blur more than distant ones.

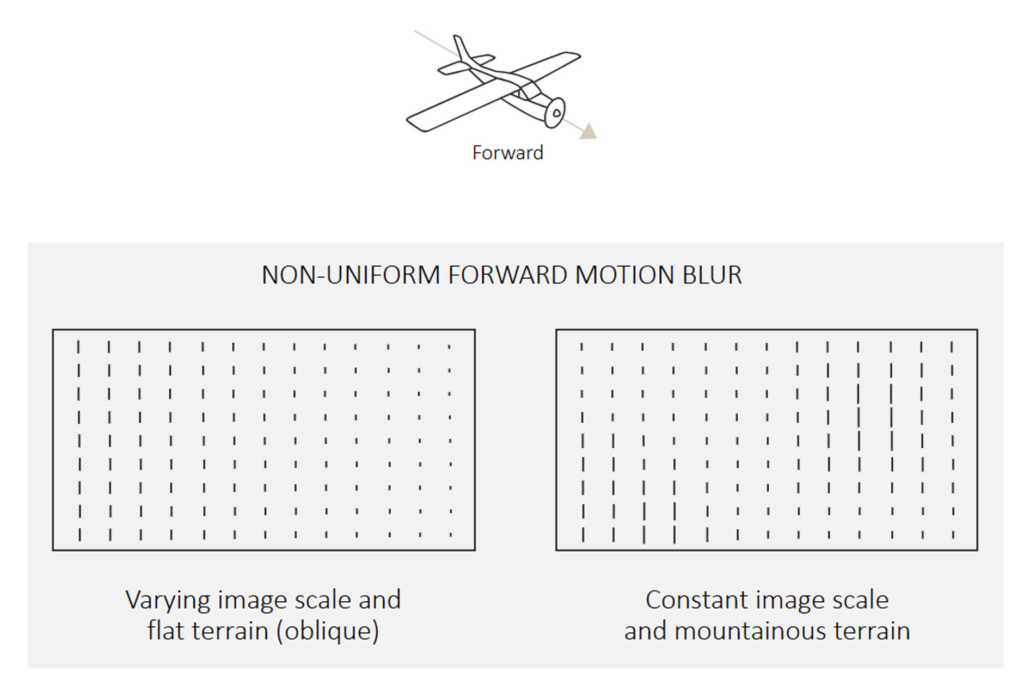

Rotational motion blur

Small changes in roll, pitch, or yaw during exposure create blur that varies in both direction and magnitude across the image.

In real flight, all three occur together. The result is spatially varying blur with every part of the image blurred differently.

Traditional motion-compensation methods were designed for the simplest case: uniform forward motion over flat terrain. That’s why they struggle when viewing angles change, terrain varies, or aircraft motion becomes complex.

Traditional Fixes and Where They Fall Short

The industry has tried several ways to deal with motion blur over the years. These older solutions try to fight blur physically or by limiting exposure:

- Time Delayed Integration (TDI) – used in older CCD sensors to compensate for uniform forward motion blur. Effective in simple cases, but limited by design.

- Mechanical motion compensation – physically shifts the sensor during exposure, but adds mechanical complexity and only addresses basic forward motion.

- Short exposure times – enabled by modern CMOS sensors, shorter exposures reduce blur but sacrifice image quality, dynamic range, or scene-dependent motion induced image blur.

All of these fail to compensate multi-directional, scale-dependent, or scene-dependent motion induced image blur.

How AMC Works (Without the Math)

Adaptive Motion Compensation (AMC) takes a different approach: it solves the blur in software instead of trying to prevent it in hardware. It uses a non-blind deconvolution process, which in the simplest terms means it knows what kind of blur occurred and how to undo it.

AMC models what actually happened during the exposure using aircraft motion, camera orientation, timing, optics, and terrain. Instead of treating the image as one blur, it breaks it into many small regions, estimates the blur in each one, and reverses it using advanced deconvolution.